A Marshy Common

The name St Stephen’s Green originates from a church called St Stephen’s in that area in the thirteenth century. Attached to the church was a leper hospital. Around this time the area was a marshy piece of common ground, which extended as far as the River Dodder and was used by the citizens of the city for grazing livestock.

In 1663 the City Assembly decided that the plot of ground could be used to generate income for the city and a central area of twenty-seven acres was marked out which would define the park boundary, with the remaining ground being let out into ninety building lots. Rent generated was to be used to build walls and paving around the Green. Each tenant also had to plant six sycamore trees near the wall, in order to establish some privacy within the park. In 1670 the first paid gardeners were employed to tend to the park.

That no parsel of the Greenes or commons of the city shall henceforth be lett, but wholie kept for the use of the citizens and others to walke and take open aire, by this reason this cittie is at present groweing very populous…

– 1635 City Assembly law.

The Centre of Fashionable Display

The Green became a particularly fashionable place during the eighteenth century, owing mainly to the opening of Grafton Street in 1708 and Dawson Street in 1723, and the construction of desirable properties in and around this area. The Beaux Walk situated along the northern perimeter of the park became a popular location for high society to promenade. Lewis’ Dublin Guide of 1787 describes the Beaux Walk as being a scene of elegance and taste. Other walks found in the park included the French Walk found along the western perimeter of the park, and Monk’s Walk and Leeson’s Walk located along the eastern and southern boundaries of the park respectively.

A Private Affair

By the nineteenth century the condition of the park had deteriorated to such an extent that the perimeter wall was broken, and many trees were to be found in bad condition around the park. In 1814 commissioners representing the local householders were handed control of the park. They replaced the broken wall with ornate Victorian railings and set about planting more trees and shrubs in the park. New walks were also constructed to replace the formal paths previously found in the park. However with these improvements, the Green then became a private park accessible only to those who rented keys to the park from the Commission, despite the 1635 law which decreed that the park was available for use by all citizens. This move was widely resented by the public.

Read More

The Ardilaun dynasty on The Peerage.

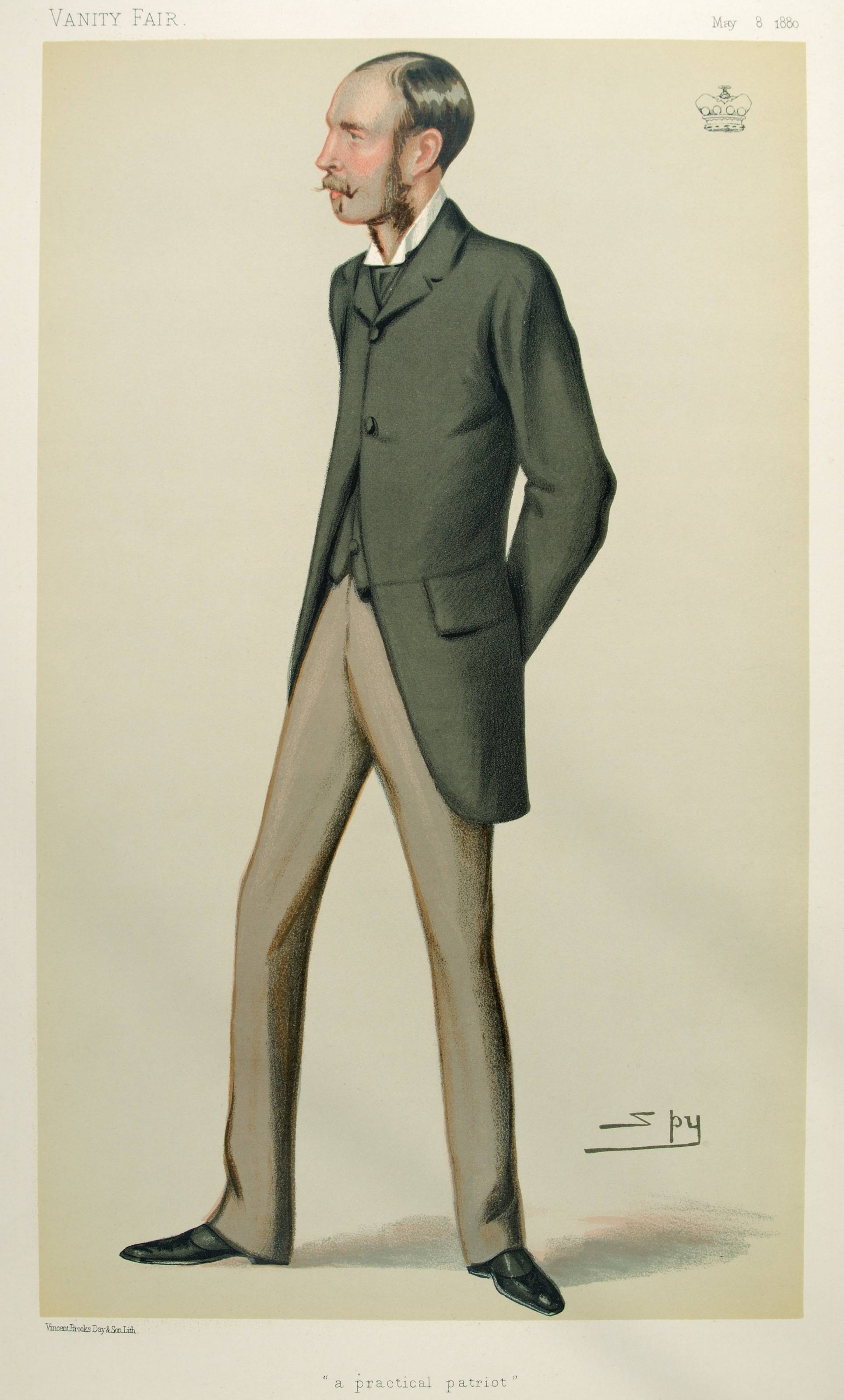

Lord Ardilaun’s Gift to the People

Sir Arthur Guinness, later known as Lord Ardilaun, grew up in Iveagh House located on St Stephen’s Green, and came from a family well noted for its generosity to the Dublin public. In 1877 Sir Arthur offered to buy the Green from the commission and return it to the public. He paid off the park’s debts and secured an Act which ensured that the park would be managed by the Commissioners of Public Works, now the OPW.

Sir Arthur’s next objective was to landscape the park, and provide an oasis of peace and tranquility in the city. He took an active part in the design of the redeveloped park, and many of the features in the park are said to have been his suggestions. The main features of the redeveloped park included a three-acre lake with a waterfall, picturesquely-arranged Pulham rockwork, and a bridge, as well as formal flower beds, and fountains. The superintendent’s lodge was designed with Swiss shelters. It is estimated the redevelopment of the park cost £20,000.

After three long years of construction work, and without a formal ceremony the park reopened its gates on 27th of July 1880, to the delight of the public of Dublin.

The picture is a truly delightful one and cannot fail to impress every visitor to the Green with the incalculable benefits which such an oasis must bestow on the city and its people.

– The Daily Express, 28th July 1880.

Download

Durability Guaranteed: Pulhamite Rockwork, its Conservation and Repair, a booklet from English Heritage.

The Easter Rising

On Easter Monday 1916 the Irish Citizen Army attempted to overthrow the governing British powers in Dublin, by taking control of strategically-important sites around the city.

Rebels under the command of Michael Mallin and Constance Markiewicz seized control of St Stephen’s Green. Trenches were dug around the perimeter of the park, and the glasshouse was used as a First Aid station. Evidence of fighting can be found on the Fusiliers’ Arch at the northwest entrance to the park, where bullet holes can still be seen to this day on the structure.

Read More

‘St Stephen’s Green and 1916’ on the NLI online exhibition The 1916 Rising: Personalities and Perspectives.

Bibliography

- McCabe, Desmond. St Stephen’s Green Dublin, 1660-1875 (2011)

- Craig, Maurice. Dublin 1660-1860 (1952)

- Fagan, Patrick. The second city: portrait of Dublin 1700-1760 (1986)

- Guinness, Michele. The Guinness Spirit: brewers and bankers, ministers and missionaries (1956)

- Kealy, Loughlin. The Georgian Squares of Dublin: an architectural history (2007)

Download

A guide to the Monuments of St Stephen’s Green Park.